My Bumper Comics Of The Year 2020 Extravaganza

I didn’t get to do my usual Best Comics of 2020 for the Irish Times, since COVID has reduced page counts all over the media landscape and the space for it was cut. BUT since my yearly round-ups (2019, 2018, 2017, 2016) have always been quite popular (i.e. I get loads of very animated people in my mentions arguing about it for a very long time afterwards, which only usually happens if you slag off the GAA or the Irish language), I thought it best to continue that momentum and stick my thoughts here instead.

The downside is I do not get paid for it which is, as we say in the industry, a real pisser. But the upside is I get to talk at greater length about comics I’ve liked this year AND feature more works than I’d ever be able to in print.

So that’s what this is! Let’s begin.

(All images sourced from the web/comixology/Kindle screen grabs and all rights belong to their creators. I will immediately remove any and all art should anyone wish me to)

BEST STING IN THE TALE

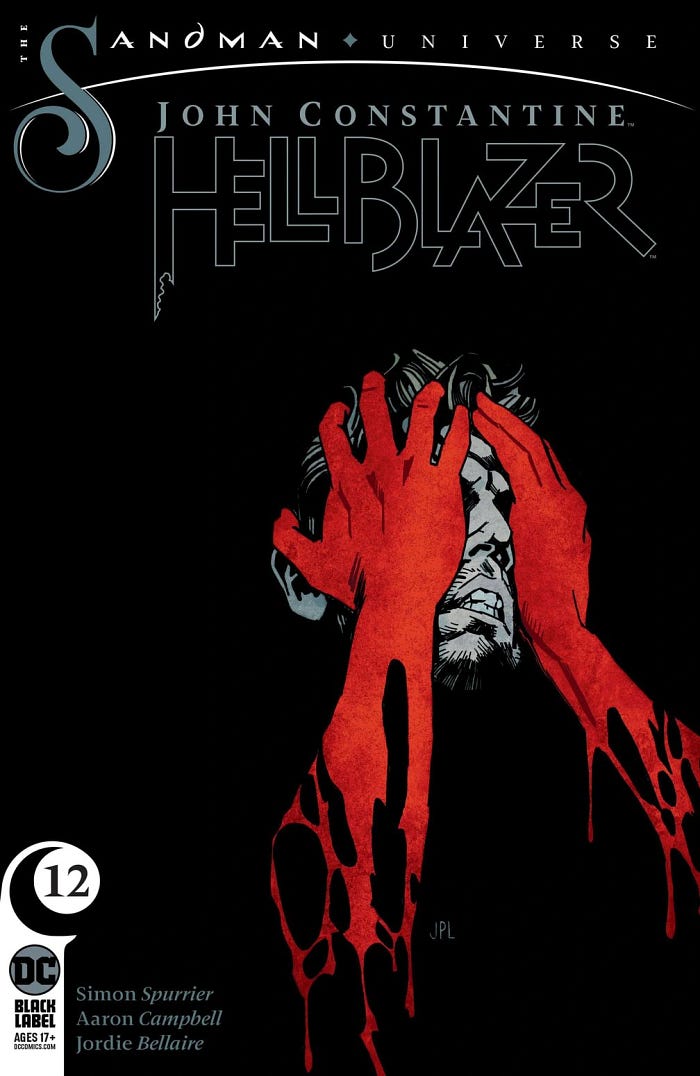

I won’t beat around the bush, Hellblazer, written by Si Spurrier, art by Aaron Campbell/Matias Bergara, colours by Jordie Bellaire and lettering by Aditya Bidikar (DC) was the best ongoing comic I read this year.

The crux of John Constantine’s appeal is he’s a magician who looks like a private detective who looks like Sting. The latter is meant literally, incidentally, since his invention was famously borne out of Alan Moore, Steve Bisette and John Totleben justifying the fact they stuck Sting in the background of an early issue of Swamp Thing, by retconning his appearance into a fully-fledged character; surly, streetwise British magician and supernatural investigator (who just happens to look a lot like Sting), John Constantine.

For reasons best known to those who later spun him off, his series was named Hellblazer and this title was stuck above his head on covers, promotional materials and industry mentions, even though he is himself rarely referred to as such in the comics themselves. This is because the name doesn’t really make any sense. If you split the noun apart, one is met with the intractable problem that blazing hell means precisely nothing, although we’d all love to imagine it refers to a particularly natty, demon-themed sports jacket, which is yet to make its eleventh-hour appearance in the canon.

BEST SIDENOTE IN THE MIDDLE OF THIS OVERLY LONG REVIEW OF HELLBLAZER

Anyway, In the past three decades, Constantine has been patchily applied in different corners of the DC Universe, as well as film and TV appearances. But he had a particularly active 2020, featuring prominently in this year’s Justice League Dark arc and also in Hellblazer 1–12, which might just be the character’s best ever outing.

In it, Constantine has returned to Britain for the first time in years, and finds the country beset with all number of maladies, supernatural and not. Nightmares come to life, fears made flesh, and some unseen hand guiding the ideated phobias and hatreds of Britain into solid creatures of violent horror. What follows is a knotty, horrifying, hilarious and heartbreaking trip through fairy tale monsters, bad dreams, vicious demons and Tory ministers, which also serves as a circumnavigation around all the shittest things about Britain in the 21st century.

What lifts all this above the level of snarky polemic is Spurrier’s uncanny knack for keeping his eye on the prize, without ever over-tipping what could be a very heavy hand. There are a thousand easy outs for people wanting to write satire in 2020, and a recurring horror of British politics especially is the preponderance of fruit that’s not so much low-hanging as piled in mouldering pyramids in every corner of the fucking yard.

So, for all its polemical zeal, it’s remarkable that Hellblazer skips past these pitfalls without scuffing its shoes. Even as it skewers white nationalism, xenophobia, NHS cuts, industrial farming and the UK’s yawning divides in wealth and class, it never seems like the wheedling, self-important whinge it so easily could. These are stories, not lectures and, without straying too far into hyperbole, it’s simply some of the best comics storytelling I’ve read in years.

Spurrier’s writing is typically excellent, mining rare depth from its characters’ relationships, and hair-raising horror from everyday terrors. The pit-of-the-stomach revelation about what exactly one brave British fisherman is supplying to his punters in issue #7 will linger a while longer than any single reveal I’ve encountered all year. Spurrier is aided in not one but two exemplary turns by gifted artist leads, in the broodingly affecting lines of Aaron Campbell, and the gloriously expressive splatter of Matias Bergara - as fine a one-two punch of artists as you could wish for. It’s a tribute to the power of each that there’s only a micro-second of disorientation every time they change hands, only to fall back in love with each during every transition.

All of which makes it practically inconceivable that the series was discontinued by DC after its 12 initial issues, for reasons which Si has gone into on his own blog, and which should sadden and enrage any reader in equal measure. He’s quick to point out that there’s no one thing or person to blame, but if there’s any justice in the world, DC will see the reaction to this series and place hope in its creators to return to the sceptred, sceptic isle. There is simply so much here to love, all you’ll want is more.

I mentioned Justice League Dark by Ram V, James Tynion IV, Alvaro Martinez, Raul Fernandez, Brad Anderson (DC) — so let me give a brief shout out to its gloriously silly, arcane plots and deeply convoluted mechanics, all topped with Ram V’s unassailable ear for dialogue that sounds like it should be written on scrolls.

For anyone who devoured last year’s These Savage Shores, V has become nigh-on unmissable, and JLD is a great exercise in getting thinky, thoughtful writers to tackle big properties for big results. Featuring Zatanna, Swamp Thing, Dr Fate, Wonder Woman, Detective Chimp, and a Constantine who swears a lot less in this — and certainly takes less pot shots at Tories and yoga-crazed tantric hipsters — although the stories are none the weaker for it.

As gloriously weird as “mainstream” DC super-team stuff could ever hope to be, it now looks like V will be taking the series on as a back-up strip for the new Justice League main series, starting in March. Which is either a demotion or a promotion or a planned marketing strategy, I simply can’t tell because the rubrics of comics publishing are even more complex than cellular parliaments meeting to discuss the battle between life, death, rot and the annihilation of the entire known universe.

BEST HULK SMASH

Immortal Hulk by Al Ewing and Joe Bennett (Marvel) has, for the past few years of my round-ups, almost been a victim of its own consistency. By that I mean, I glossed over just how much I enjoyed it in the year-end chatter because I’ve already gone over how much I love it each previous year, and there are so many great spangly new things to talk about that repeating myself about one series seems redundant.

This is a patently stupid approach, since the very fact that I’ve been enjoying Immortal Hulk for so long, while some of those spangly new breakout titles from previous years have withered on the vine, suggests it’s actually more worth talking about than the hot new kid on the block. Also, since Medium has no word limits —though they may consider enforcing them after I publish this-I can afford just a few extra syllables to recommend Immortal Hulk yet again.

Immortal Hulk’s premise, if you’re not aware, is simple. It takes that old complaint levelled on superheroes — they can’t die so what’s the point? — and turns it into something existential — I cannot die, what is the point?!?. It posits that a bullet to Bruce Banner’s brain, or any fatal blow, will kill him, but not the Hulk, who will rise again, forever undying, rendering both he and Banner, effectively, immortal.

Thereafter, it follows this thought to its conclusion, not merely as a schlocky power fantasy, but a horror of possession and personality disorders that takes proper delight in body horror. Hulk is mainstream superheroism’s werewolf, Hyde, Gremlin type — he has transmogrification baked into the text. But Immortal Hulk takes a pride, nay, a perverse ecstasy in the grisly, bloody, sinewy splatter of gore and guts that this transformation would entail. The stories themselves unfold mostly in a Monster Of The Week format, with several overarching strands of a greater story looped over the top. It’s one of the chewiest, grisliest titles on the stands and if you haven’t dug in yet, I simply don’t know what else to tell you.

BEST WHILE-WE’RE-ON-THE-SUBJECT-OF-GOOD-MARVEL-COMICS COMIC

Daredevil by Chip Zdarsky, Marco Checchetto, Jorge Fornes, and Francesco Mobili (Marvel) has also been a riveting read, relying less on the pyrotechnics of other ongoing series, and more on laser-guided storytelling and a wilingness to engage with some of the more apparently contradictory notions inherent in superhero genre; if you go around beating people up for a living, what happens when one of them dies? To what extent does the entire idea of fighting crime with violence make sense on either a moral or practical level? And what actually separates a street tough who breaks one nose to make a few quid and a guy who breaks a dozen (and destroys every building he’s in in the process) just because he has a hero complex?

The extent to which Zdarsky and co’s Daredevil actually answers any of these questions satisfactorily is up for debate, and you will be shocked — shocked I tell you — to discover that Daredevil’s repeated vows to reject violence are short-lived, but their canny way with such quandaries makes for a compelling read. Yes they have their cake and eat it too - but it’s good cake, Brant. Not least the parallel subplot, featuring Wilson Fisk as New York mayor, experiencing the power, and eventual degradation of public office in 2020- something a certain omni-disgraced former holder of the title “America’s Mayor” can likely attest.

MOST AMAZING HAHAHAHA HAHAHAHAHA HAHAHAHAHAHA

BEST USE OF METROPOLIS’S FINEST

Superman Smashes The Klan by Gene Luen Yang and Gurihiru (DC) is every bit as engrossing as its title suggests. Adapted from a 16-part arc in the 1940s Superman radio serial - The Clan Of The Fiery Cross, broadcast June to July 1946 — it tells the story of a young Chinese-American family subjected to racism in ‘40s Metropolis, and Superman’s quest to uncover the ringleaders of the shadowy cabal of white supremacists leading their abuse. The original radio series is noteworthy for having been supplied information from activist and civil rights campaigner Stetson Kennedy, who infiltrated the real life KKK and divulged details of their rituals, codewords and grotty organising to the makers of the massively popular radio serial, so that they would be trivialised and demystified to its audience of millions each evening.

By some accounts, it wounded the Klan so emphatically that their membership was decimated and never quite recovered, by others it was merely a neat exercise in using light as disinfectant that has subsequently been over-egged by “this cool thing from history” podcasts, only to then be passed on as fact by people like me who listen to too many “this cool thing from history” podcasts. Either way, in an America newly awake to the threat of open, organised racism, Superman Smashes The Klan packs a timely Ka-pow.

The story is centred on the family Lee, and on Superman himself, very much clad in the powers and stylings of his ‘40s self. When we meet him, he can leap, but not fly, and he comes readymade with the twinkle-eyed, aw shucks patter of a kindly, well-meaning uncle. Post-80s-grimdark-tortured-son-of-a-murdered-planet-Superman this is not, even though this Clark Kent is certainly intrigued by the sense that there’s more to his powers — and their otherworldly origins — than he’s been led to believe.

In a story about racism, hatred and prejudice, this mapping of the character works surprisingly well, for several reasons. For one, Yang’s home-spun dialogue works perfectly to ground the story in the trappings of its time, just as the 1940s serials did. By drawing this Norman Rockwell image of mid-century America in all it’s soft-focus glory, Gurihuru’s art serves as neat — even ironic — counterbalance to the horrifying realities it often describes, and works to demonstrate that racism is not limited to shadowy, vitriolic hill-billies and angry louts, but can be found in the corn-fed, smiling citizens who smile through church but just don’t understand “what’s so wrong about wanting to live with your own kind”. That this is still relevant 75 years later is sad, but also makes for essential, and addictive, reading.

Fans of The Big Apricot at its most rakishly technocolour will delight in Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen by Matt Fraction and Steve Lieber (DC) which is still, pound for pound, the most engaging, joyous and gonzo superbook in print. As I said in my Irish Times review of 2019, the joy in SPJO is in the sheer delight Fraction and Lieber take in generating laughs from the DC canon without ever lapsing into sneering mockery. And the laughs are not, it should be said, of the smirk or sly chuckle variety, but proper, stupid, chuckling glee.

I MEAN COME ON

Much of the series’ comedy is mined from Fraction’s whip-smart scripts, which traverse the absurdity of canon characters and behaviour, and mash together unexpected figures — the Porcadillo being a standout — with the self-serious narration of Silver Age Supertitles. Multiple times within each issue, the reader is delivered cliffhangers and act breaks (lavishly lettered by Clayton Cowles, clearly having a ball) which manage to wring comedy from even the formatting of traditional comics, and the design and pacing of the strips of Jimmy Olsen’s 60s heyday. The cumulative effect is a series that fits the gutbusting void left by the departure of Unbeatable Squirrel Girl last year, and proves that there’s nothing so seductive as a book that’s willing to be sly, stylised, and seriously, seriously, silly.

BEST DESCRIPTION OF A BOOK’S LORE THAT READS LIKE IT’S BEING DELIVERED BY AN OUT-OF BREATH NINE-YEAR OLD WHO’S HEARD YOU LIKE COMICS

Shout out the absurdly info-packed X of Swords Handbook which is 60 pages long and never drops this exact Previously, On Everything That Has Ever Happened pace at any stage.

BEST ARTY COMING-OF-AGE TALES THAT ARE EVERY BIT AS GOOD AS THE REVIEWS SUGGEST

When Sophie Yanow was a student, she took a semester in France and set off from Paris for a hitch-hike across Europe. On this trip, which forms the basis for The Contradictions (Drawn & Quarterly), she was accompanied by a new friend Zena, a charismatic, fixie-bike sporting anarchist. What follows is a warm, funny coming of age tale, that explores ideas of privilege, capitalism and sexuality, without ever seeming preachy or didactic.

This is a book filled with small moments of discovery. Yanow is a master at wringing achingly funny depictions of the awkward, sometimes insufferable, pretentions of student life, while also conveying a real empathy for those who express them. The Corrections won an Eisner award as a web-series but the story works just as well at novelistic length, as Yanow’s knowing dialogue and clear line style bring her plot to life with unfussy panache. A lesser author might over-egg the characters’ circular agonising, their endless navel gazing around capitalism, or their own yawning privilege, but Yanow takes her time to show the virtue of these principles, and the people who hold them, where others might have made them insufferable cliches. The Contradictions’ characters are, yes, contradictions. But, while they may be cartoons, they’re never caricatures.

A Map To The Sun by Sloane Leong (First Second) is another beautiful coming-of-age tale centred on five girls who start a high school basketball team, dipping in and out of their struggles through family life, young love, and the quotidian traumas of teen friendships. Leong’s neon colour pallet works extremely well in conveying the heightened emotions and deep feelings of adolescence, and stands in marked contrast with the darkness explored in their lives. Her language, too, cuts deftly between the poetic, dreamy descriptions of a distant, perfect summer, to the everyday humiliations of high school life, poverty, and domestic dysfunction.

It’s Leong’s descriptions of the sway and swell of friendships which are most beautifully realised. The push-pull drama of competing affections, the messy and sometimes arduous process of liking people and hoping they like you back; a subject so uncannily familiar to anyone who’s ever been sixteen — or has ever had a friend — it’s alarming it’s so rarely addressed in comics, let alone with this kind of depth and heft. A Map To The Sun is a burst of bright light in the dark, and a blast of warmth through cold, callow youth.

SPEAKING OF WHICH, Y’KNOW WHEN THIS HAPPENS?

Do some comic artists use fakey versions of brand logos just because they don’t want to promote companies for free (fair enough) or is there some copyright thing at work (also fair enough, I guess)? Answers on a postcard!

BEST EXTREMELY BAD ADVERTISEMENTS FOR BECOMING A CARTOONIST

The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Cartoonist by Adrian Tomine (Drawn & Quarterly) is more heartbreaking than a book this funny has any right to be. It’s a segmented memoir that charts Tomine’s life and career, from his neurotic younger days all the way to his present, still quite neurotic, days and does so via a series of short chapters titled with their time and place — San Diego, 1995; New York, 2011 etc — placed within the text as short vignettes. Each may only last three or four pages but, taken together, they trace a compelling, often hilarious, path through the ongoing humiliations of writing, drawing and promoting comics.

The name-calling and wedgies of adolescence are merely a prelude to the indignities of promoting his work in the convention circuit, appearing at empty book signings and sitting through award ceremonies where he never wins and his heroes either refuse to attempt the pronunciation of his name or offer Tomine — a fourth-generation Japanese-American — an unmprompted account of their love for Jiu-jitsu. The entire book is shot through with self-effacing humour and several bravura moments of cringe comedy, such as his toe-curling experience of being interviewed on NPR’s Fresh Air while in view of a dental surgery, which prompts an out-of-body experience.

I spoke with Tomine about the book earlier this year and it was striking how weird it felt to be doing the very same thing he described in Loneliness, but if he was as nervous about that as he was when he was interviewed by Terry Gross he put a brave face on it. For that, as much as anything else, he has earned my undying respect.

Some similar ground is coverd in Paul At Home by Michel Rabagliati (Drawn & Quarterly), albeit in very different form. Paul is a fictionalised author-surrogate for Rabagliati himself; an aging cartoonist who, like Tomine, suffers certain indignities at book signings and struggles through the financial insecurities of magazine illustration work. In Paul At Home, however, these issues are focused into one place and time, as we find our protagonist divorced and contemplating mortality in the guise of his dying mother and the increasing distance between himself and his adult daughter.

Rabagliati’s script and clean lines acutely convey the particular pangs of middle age, often excruciatingly sad while still being beltingly funny. There’s a lightness of touch that seeps into every page - small shots of a tree in the seasons, the gradual rusting of a swing set - and the uncommonly smart dialogue, in which each conversation feels like real, unmannered speech— even more impressive, given I was reading it in English translation (shout out to translators Helge Dascher and Rob Aspinal!)

Although Rabagliati’s Paul books are bonkers massive-sellers in the Francophone world, this was the first I’d actually read but I will immediately be tracking down as many more as I can, perhaps working my way backwards so I can watch him gain hair, money, wives and spangly new swing sets, as yet unbothered by the gathering rust of passing years.

BEST WHATEVER THIS IS

It’s hard to know what to say about Portrait Of A Drunk by Olivier Schrauwen, Florent Ruppert & Jérôme Mulot (Fantagraphics), a book for which no description seems adequate and any attempt risks spoiling its fantastical effect. The joy begins with the front cover, and the gurning face that stares from it. This is, for my money…

THE MOST PURELY ENJOYABLE IMAGE COMMITTED TO A HARDBACK COVER IN 2020

- but its simple delights bely the dark, rotten heart of the story’s titular lush.

Our protagonist, Guy, is indeed a drunk, but he may also be one of the most reprehensibly amoral characters you’ll meet this year; a ship’s carpenter by trade, an alcoholic by habit, and an utter bastard by something like vocation.The book follows Guy as he blithely cheats, lies, murders and steals his way through 18th Century France, its overseas colonies, and the wide blue oceans between. We also meet the souls of his departed victims, cursed to watch his shabby misadventures through an ever-shrinking aperture in purgatory, whence they narrate his activities in the manner of a slowly decaying Greek chorus of corpses. Things only get stranger from there but, suffice to say, the book’s all the better for every gruesome and gristly bit of it. Portrait of A Drunk is an utterly compelling, startlingly original, and bleakly hilarious book. Rarely, if ever, has ugly been so beautiful.

BEST FAMILY YOU MIGHT WANT TO JOIN AFTER READING

Shame Pudding by Danny Noble (Street Noise), is a book I love so much I find it hard to measure. It’s a family memoir which tells the story of Noble’s own clan, starting with her grandparents’ generation of Polish Jewish emigres (to Hull, and later Brighton) who populate family meals, funerals, weddings, and religious holidays.

The book’s early passages are told from the point of view of the author’s infant self, framing big-picture family dramas within the instinctive, intuitive, logic of a child. It’s exhilarating to trace a six year old’s description of “great aunts with large glasses” or “uncles with massive ears” and feel the tracks of their train of thought beneath your feet. That it manages to do so without ever becoming obtuse or self-conscious, is testament to Noble’s skill as a writer. That you grow to love every scratchy, scribbly drawing is a tribute to her art.

This is a book that exudes giga-watts of warmth, all while providing more laugh out loud moments than most out-and-out comedies. The title itself stems from the term of endearment used by Noble’s grandmother for her grandkids, a mispronunciation of the Yiddish “shayn punim”, or “beautiful face”. Like the phrase itself, Shame Pudding is a sincere and lovely thing which, even when it translates to something silly or absurd, never loses its sweetness.

BEST COMIC FROM THE ACTUAL FUTURE

Dominican-born Toronto native Freddy Carrasco is redrawing science fiction, with Gleem (Peow Comics) an all-black, y2K-futurist landscape of religious visions, dance floor ecstasy, and intermittently explosive robots. Gleem drops you very much in media res, with little by way of introduction or exposition, and sends you falling, tripping, bending and flying through its futuristic vistas, extending for pages at a time with little dialogue. The result is as captivating as it is bracing, following lead character Femi through three stages of his life; accidentally imbibing narcotics at a religious service, attempting to replace a much-loved android, and experiencing the wordless, hallucinatory intensity of a space-age rave confined to a nightclub bathroom stall. The first and third of these, in particular, show an uncanny awareness of movement and action, as Carrasco’s fluid, inky, black and whites melt time and space in your hands. The effect is as close to moving images as the printed page allows.

If that all sounds bewildering, it’s barely the half of it. Gleem offers that captivating feeling common to all great sci-fi: a sense that its world expands above and beyond the page, inviting us to view just one small glimpse at its reality at a time. And it’s time well spent, so expect to read and re-read it, until time and space fold back on themselves anew.

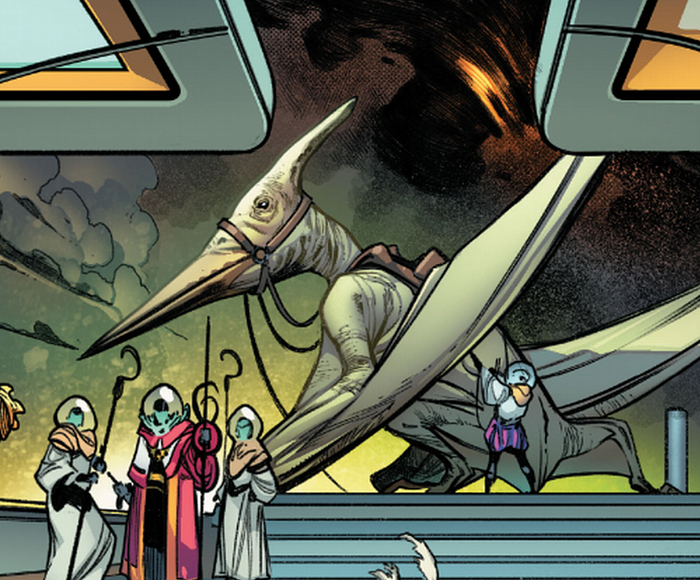

BEST UNIVERSES IN YOUR POCKET

Decorum by Jonathan Hickman and Mike Huddleston (Image) is a very Imagey book, and I mean that as a good thing. Set in an giant cosmos of Hickman’s creation, it’s the story of Mrs Morley, “the universe’s most well-mannered assassin” and her travails through the high tea and lowlives that form her bread and butter, as well as her quest to blood in a new recruit to the Righteous Guild, a galaxy-hopping syndicate of murderers-for-hire.

Some of the high-English dialogue is slightly too arch for its own good, but as speculative scene-scetting goes, this is [deep inhale before passing] the good shit. Decorum features the kind of knotty, ten-feet-deep world building Hickman can do in his sleep; the sort that makes you imagine he has fifteen of these fully baked universes in his back pocket, ready for use any time he needs. That sounds like faint praise so I want to make it clear it’s a compliment, and one of the things about Hickman I truly love.

I don’t know the man, but he strikes me as the sort of guy who loves nothing more than tracing a focused finger over the maps and charts at the start of a fantasy novel, or poring over the deep-world info in an adventure game, i.e. like I do. I made a tongue in cheek gag at the expense of the X of Swords Handbook earlier — a series I’ve still not really gotten under the skin of — but I’ve even done this for Hickman’s own work, with the “The World” handbook he wrote for East of West, to which I lovingly referred throughout the early days of that series. Decorum dispenses with the idea of a separate handbook by simply having little data-heavy pages interspersed within the text, which explain worlds, societies and races in beautifully layered text, adding a great deal of depth while also breaking up the narrative into digstible chunks, a bit like a game’s loading screen. The result is a book that never tires the mind, no matter how much info is unloaded, a great deal of the praise for which might go to Russ Wooton on letters and Sasha E Head on design.

What makes this truly sing is the staggeringly gorgeous and varied art by Mike Huddleston which bends style and form so freely each issue feels like an anthology featuring half a dozen artists, each desperate to outdo the last. I’m excited to see where it goes next.

Speaking of world-building powerhouses, posibly my favourite imagined universe of the year is Far Sector by N.K. Jemisin and Jamal Campbell (DC), a Green Lantern story comprising almost entirely new characters and lore. This is, effectively, a procedural mystery contained within science fiction trappings at their most conceptual. Lantern Jo Mullein, originally from Brooklyn, finds herself on the beat of a distant world — the far sector of the title — made up of the remnants of three races whose former warring had destroyed their previous homeworlds. In order to placate these antagonistic species — respectively; vaguely reptilian humanoids, anthropomorphic carnivorous plants, and a species of sentient artifical intelligences — the society has accepted genetic programming which undoes all emotion, meaning Jo does not just feel like a stranger in a strange land, but is also the only person on the planet legally allowed to feel… anything.

The concept is beautifully conceived and expertly deployed, without ever getting in the way of the story, or its action setpieces. Jamal Campbell’s art is also extremely adept at taking this heady mixture and making it leap off the page, conveying the idiosyncracies of these peoples, alongside some truly stunning comicbook thrills. All of which means Far Sector is probably the book this year for which I was most upset to run out of issues, which is about as high a compliment as I can give.

BEST CONFIRMATION OF HOW A LOAD-BEARING WAR-PTEROSAURS PROBABLY STANDS, IF YOU THINK ABOUT IT

I’ve got to go for a two-way tie between X Of Swords…

And Decorum…

But I think we can all agree it’s a huge year for this category, which hasn’t seen such competition since this one panel from 2018’s Paper Girls #22.

Expecting big things for 2021.

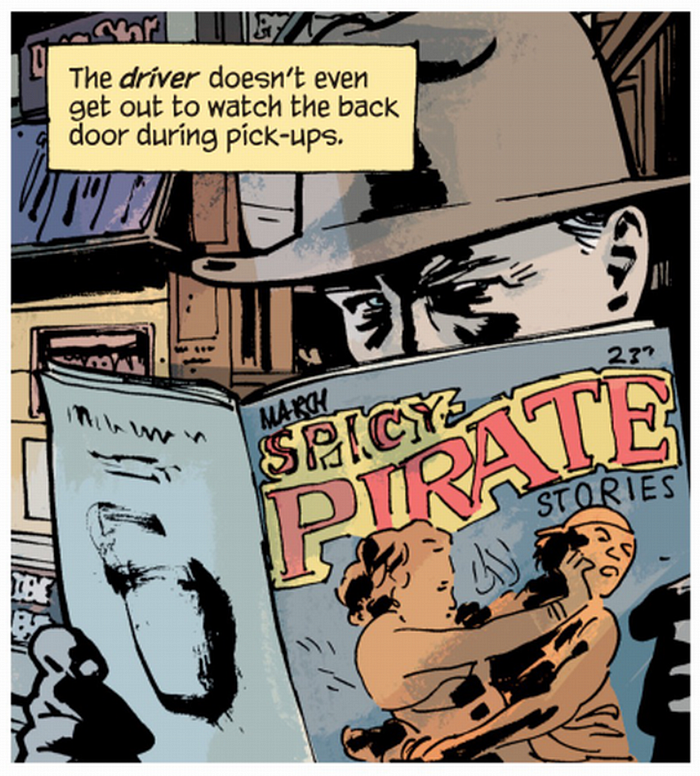

BEST DEMONSTRATION THAT THE SECRET INGREDIENT IS CRIME

Criminal by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips (Image) — What can be said about Criminal that hasn’t already been said about finding a tenner in an old coat pocket. It’s an unassailable, undeniable good, that really needs little further recommendation than I can give it here. Brubaker and Philips have cornered the market in terse, layered, psychological studies of the low lives and high misdemeanours of their grotty little universe, and a decade into their life of crime these tricks has lost none of their cham.

Brubaker has that rare,Busiek-like knack for being able to foreground his stories with extremely heavy narration without the result ever lapsing into a disconnected buffet of words and pictures. There’s a grubby, grotty, tension to Phillips’ art that fits — or rather sets — the mood of Criminal; a literal rogue’s gallery of haunted faces, sullen betrayals, and gap-toothed cons ratfucking their way to the next big score. His illustrations also give fine expression to the series’ other killer app: the end-notes section of each issue, in which guest essayists talk about a great crime or noir flavoured film, which quite simply every comic should do.

This year also saw their standalone graphic novel, PULP (Image), which arranges many of the same notes on a sightly varied theme; namely the story of a washed-up writer in the 1930s, parlaying his past as an 1890s cowboy into a middle-tier career as a writer of cowboy paperbacks. He loves his wife and hates Nazis and the result is a book that makes you want to read a full-length Brubaker/Phillips western series, or a turn on every imaginable trope and style for that matter. Romantic comedy next, please.

BEST FICTIONAL COMIC-WITHIN-A-COMIC THAT’S SHOWN FOR PRECISELY ONE PANEL BUT WHICH I’D BE EXTREMELY EAGER TO READ IN FULL

BEST PROOF THAT DER’S MORE TO IRELAND DAN DIS

It’s quite possible I love Scarenthood by Nick Roche and Chris O’Halloran (IDW) more than any other comic on this list. For a few reasons. Firstly, it’s unmistakeably and unapologetically Irish, both in setting and tone, which is remarkable for a big title, and also perfectly appropriate for the story it’s trying to tell. But Scarenthood is, at root, a light-horror mystery, centred on the experiences of a group of parents drawn together by a shared school run, and a preponderance of spooky occurrences blighting their small community.

These are lovingly rendered characters, full of the tics and asides of Hiberno-English that will be as delightful to visitors as they are familiar to natives. Scarenthood’s brand of, well, scares, is also beautifully pitched to readers of a certain age who’ll know of the terrors that sit deep in every parent’s heart, from the deep-set belief that we’re fucking everything up, to the mundane, but no less potent, horror of having to make friends after the age of thirty. I missed out on Scarenthood for my Irish Comics write-up for the Irish Times this year, cos I hadn’t read it at time of writing. I felt pretty bad at the time, and worse now. This is a series I will be devouring each day it comes out, and yet more evidence that the Celtic invasion of comics is still very much in Tiger mode.

Speaking of that Irish Invasion article, I’d be remiss not to go over a few of the things covered in that piece here and now, as the current crop of Irish artists and creators is so massive, it’s hard to reckon with. They also all seem to really like each other, which is bad news for a journalist wanting to stoke resentments for a scandalous expose, but good for anyone who wants to fondly imagine a dozen or so Irish comics big shots living together in a giant commune. As colourist Derbhla Kelly put it when I suggested this to her, “I do actually have a bunch of American comics pals who say they want to all come live in a big house together in Ireland about once a week, so I guess we do give off that vibe”.

Many of the works I featured in that piece were discoveries for me, and are worth bigging up any time I get the chance, like…

Americana by Luke Healy (Nobrow) was one of my favourite works of 2020, even though technically came out last year (there is, in fact, nothing technical at all about that distinction, it simply came out in 2019 but I don’t give a fuck about anything). It’s a memoir of his own attempt to hike the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2,600 mile hike that spans the US’s entire west coast. This is, in a very literal sense, a book about distance, whether that be length between checkpoints on a dusty path, or the emotional gulfs between people seeking splendid isolation on this arduous, sometimes punishing, journey. It’s a long, long road but Healy is, fortunately, a delightful companion, and succeeds at capturing the struggles — and solace — inherent in walking for an extremely long time for no good reason.

Americana’s pace fits its theme. Stately and measured without ever being ponderous, it allowing space for a hundred quiet little character moments that reveal a writer of true craft. Healy’s cartoony drawings are so beautifully rendered, you might only realise afterward that every single one is hued entirely in the red, white and blue of his host nation. It’s a long book, but you stand a good chance of loving every page. One of the finest bits of graphic memoiring you could ever pack in a 12 kilo napsack.

Nazferatu by Wayne Talbot and Kevin Keane (Rogue), a WW2 horror actioner, in which a vampiric villain descends upon two soldiers hoping to infiltrate a Nazi weapons factory. Published by Dublin’s Rogue Comics, it’s a lovely offering of pulpy delights for you to sink your fascist-bashing teeth into.

Treasure Island by Hugh Madden is a page-by-page graphic retelling of Robert Louis Stevenson’s adventure classic. Released entirely via his Twitter (@hughmaddenart) it’s gorgeously drafted in a squiggly, cartoonish style pitched somewhere between Hayao Miyazaki and Nick Park. This is all-ages fun that will have you scrolling for hours, and all for the price of a few taps of your thumb. Best of all, after a Herculean effort during lockdown and beyond, the entire saga was finally finished just before Christmas. Parcel out a tot of rum and read it from start to finish here.

Bog Bodies by Declan Shalvey and Gavin Fullerton (Image) was another banner title in Irish comics this year, an all-gael crew of artists (with Rebecca Nalty in tow as colourist). It’s ostensibly a gritty tale of gangland vengeance in the Dublin mountains, but it’s also a meditation on grief, guilt and maybe something approaching ghostliness. It’s mainly just one of the year’s best, and most uncompromising, graphic novels, and almost certainly the only one that opens with an excerpt from the RTE news. It also features a lot of bravura Irish swearing that made me miss home all the more.

Finally, in my interview with Declan Shalvey earlier this year, I was delighted to discover the process which led to so much Hiberno-sweariness making the edit. Quoth Shalvey: “The editor did say at one point, ‘you’re using the word ‘f**k’ so much, it’s not having an impact any more’.

I was like ‘oh, that’s fine — Irish people don’t use it for impact, it’s punctuation’.”